Year 1916

A wave of prosperity hit the country. Farmers grew rich. Cattle brought $18, hogs $22.70, and sheep $20 per hundredweight. They were spending money recklessly, for such prices were never heard of before. Commission firms grew wealthy. Common labor commanded $1 per hour. A spending spree spread over the nation, and the South St. Paul Stock Yards were no exception.

At the end of the Ice Carnival, the South St. Paul Stock Exchange gave a great banquet at the St. Paul Athletic Club rooms…. There was a long canvas sign eight by fifty feet long which read: “Calves will come, Cows may go, and the Bull goes on forever.”

There was an uproarious crowd. It was very noisy in the aisles. The brightly lighted lobby at the club’s entrance was a glare of yellow radiance. The streets were crowded. It was a jolly crowd participating in festive attire. It seemed that they all felt and acted as though the earth was perfect, as though no sorrow was possible, as though life was worth living.

Beauty abounded. The American civilization was in full bloom. Colored paper streamers were thrown between the tables like long fishing lines, curling round the bodies of dignified men and elegant women who in their gaiety found no offense in such entanglements.

Perfect strangers saluted, teased and slanged [sic] one another. In spite of the cold, thousands of people were milling around on the sidewalks in front of the club entrance. Many of them had rubber balloons, paper horns and wriggling noise devices and confetti. It was a jolly carefree mass of humanity.

David offered Albert $75 per month as a drawing account and an interest in the business, but Albert turned down that proposition. On September 16 Helen came home from Normal School very disgusted and in a grumbling mood about the home. She seemed upset and could find no [peace], as her mind was set on going to Chicago to a dancing school to study for the stage.

On November 30th Helen acted like a raving maniac. She grabbed a butcher knife from the kitchen table and said she was going to carve up Mose. She soon dropped the knife on the floor, ran upstairs and fainted, lying on the floor helpless.

Lena became skeptical and she wondered if there was any truth in what people [i.e., Shakespeare] said – that there is a tide in the affairs of man which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune . Her disconcerting perception disturbed her in regard to Helen who was one that carried hell and heaven about with her.

What we’re omitting from this edition is David’s many long historical passages which also round out his picture of the times, as well as indicating what’s going on in his mind while documenting the family story. For example, in this section, David includes several pages on Upton Sinclair and how his book The Jungle affected the meat-packing industry in South St. Paul.

“The American civilization was in full bloom”: what could this sentence mean to him? Should we see the sentence as more about the USA or more about his own integration into South St. Paul society?

Helen is now about twenty years old. She has spent one or two years being trained as a teacher of “subnormal children,” an occupation looked down upon by her father (even though he or Lena steered her in that direction, according to my mother, who says “they sent her” to the school “for the deaf and dumb.”(They had to prepare their demon child for some kind of work, as her desirability as a wife seemed questionable). Helen’s dream of being a dancer, meanwhile, had been with her for years, but been derided by her parents. If we put ourselves in Helen’s place, it’s not hard to imagine that she must have felt trapped, her window of opportunity closing as far as pursuing dance was concerned. I’m not trying to defend a “raving maniac,” but surely the truth lies somewhere in between. What I want to know is, what did Mose do to warrant a knife attack?

“Lena became skeptical”: What could this sentence possibly mean? And the next one is hard to understand too.

A bit of a stretch to relate it to the source, but it may mean that Lena is conflicted (or this may be David’s interpretation) over Helen’s personality and desires. That is, Helen is talented and ambitious but moody and antagonistic, and perhaps her wish to become a dancer is the “tide” that might be best to follow? I assume Helen was teaching at the WSNH while taking college classes at Normal School.

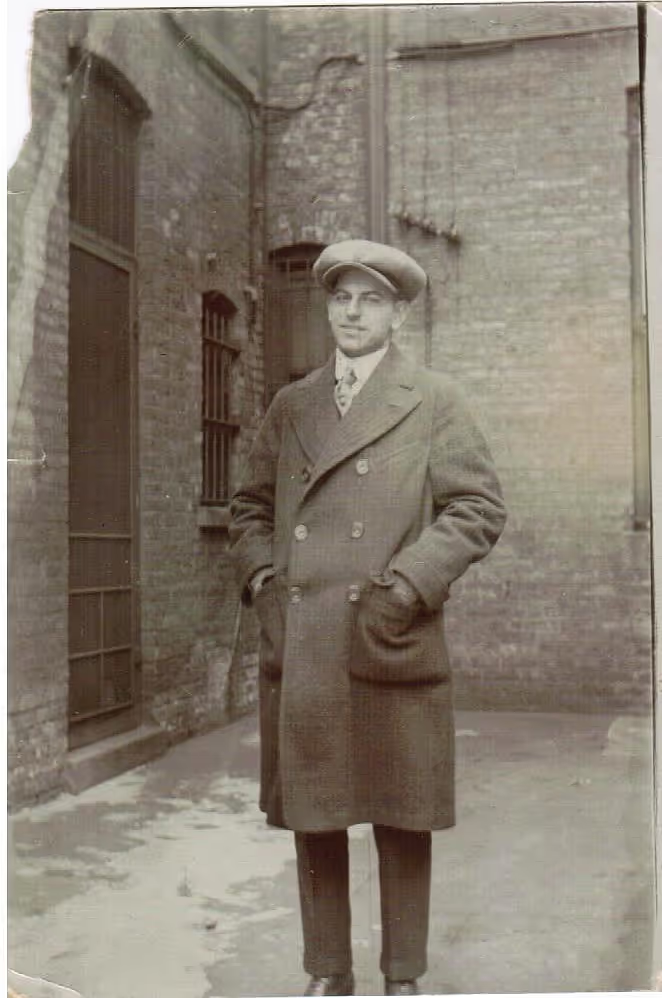

Helen had met [a boy named Arthur Singer] while she was teaching a class in the West Side Neighborhood House in St. Paul once a week. Arthur was a dark-complexioned youth with a smooth forehead and thick black hair combed back in pompadour style, slender high nose and fully lipped mouth. He had a genial face with dimples in his cheeks whenever he was laughing. He seemed to have been cut out for a clergyman or actor. From his West Side companions he acquired Russian Communistic ideas, almost anarchistic, in regard to some aspects of life.

He scoffed at all religions, saying, “Those God’s lieutenants [are] creating gods to suit their own creeds with their own rituals to suit their own creeds, inspiring fear and hate against other sects.” He frequently indulged in card games. Conversationally he was bitter against Capitalists, as he said their system is only used to extract blood from the workingmen.

Arthur was not one that was perturbed one whit – at least outwardly – by a polite reminder of his defects. He laughed easily. He was a most impenetrable youth. There was nothing to indicate him worthy of trust or friendship.

This paragraph is proof positive at any rate that David’s powers of physical description were accurate. My grandfather, Arthur Singer, was a handsome, genial man with a tremendous sense of humor. He loved debate for the sake of debating. My mother said that he used to introduce a topic and then ask his companion, “Now, which side do you want to take?” When Helen chose Arthur, she chose a man whose temperament and outlook on life was quite opposite to David’s.

Fascinating that he uses the term “clergyman” rather than “rabbi,” and that he uses the phrase “Communistic ideas... in regard to some aspects of life”; in other words, Communism was understood to have lifestyle implications — what precisely could he have meant? Sexuality?

I think he’s putting Christian clergymen, actors, and other brands of snake-oil peddlers in the same category here; Arthur Singer and his ilk were not “worthy of trust.”

I can only imagine what David might call a “polite reminder”! As for Art’s politics, I remember him saying that he was proud of the fact he’d never voted in his life. “What for?” he laughed, “They’re all the same!” He dropped out of school in the 7th grade, I believe, but was incredibly well-read.

The World War

Albert, David’s oldest boy, now a sergeant of the University cadets, became all excited at the prospect of war with Germany. His excitement burned in him and he longed to enlist. Tales of great movements shook the land. These might not be all glory, but he knew, as he read of marches, sieges, conflicts and battles, that he longed to see it all. His mother discouraged him. She looked with contempt upon the quality of his ardor and patriotism. She could calmly seat herself and with no apparent difficulty give him many reasons why war was unimportant, saying that he could be of more use at home than on the battlefield.

At last he made a firm resolution against his mother’s arguments, saying to himself, “I don’t want to be stigmatized as a draftee. My pride forbids and I shall voluntarily enlist.”

“Albert, you are a fool,” his mother told him.The young man imagined himself as an officer in an O.D. [olive drab] uniform with brass buttons and stripes on his shoulders.

While walking absorbed in these thoughts, a peroxide blonde-haired girl made fun of his martial appearance, but there was the black-haired Ruth, who gazed at him steadfastly and grew sad at the sight of his khaki uniform with the brass buttons. He had turned his head and detected her watching his departure.

Albert was sent with many others to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. Though suffering with a cold in the head at the time, he was put with others in tents. The men were inoculated systematically against typhoid fever, and many fainted from the effects of the first inoculation. These had to be repeated on some on whose systems it took no hold. The poor solider boys wept under the lash of the corporal’s tongue. Into those soldiers’ eyes came a terrified look.

Their necks were quivering with nervous weakness and the muscles of their arms felt numb and bloodless. Their hands seemed large and awkward and there was a great uncertainty about their knee joints after their long and steady drills. They felt like slaves toiling in the temple of the War Gods. They even began to feel somewhat rebellious toward their hard tasks.

Year 1917

On April 4th, David was elected by the largest vote to the South St. Paul school board. On April 6, after an exhaustive diplomatic correspondence, President Wilson signed an official declaration of war against Germany and her allies in the name of the people of the United States.

In August, Albert was transferred to Fort Snelling, Minnesota, a camp near his home. In September the United States government received a request from General Pershing, head of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, to send him better trained young officers from the new training camps. The first two training camps had been composed mostly of sons of politicians, rich men’s sons and dissipated youths who were expecting swivel-chair positions and were wholly unfit for actual field command.

In order to add better officers to the ranks General Pershing recommended that soldiers be picked by competitive examination and that a course of intensive drill be given them in the officers’ training camps to ensure better men. All commissions should be given for merit only.

Albert was one of the many successful youths chosen and he was sent in October to the third officers’ training camp at Camp Custer, Michigan, where he received an intensive training during the cold winter months. Albert was commissioned a first lieutenant and was retained as drillmaster on account of his University cadet experience.

It appears that Albert failed in Chicago too and came home. As for the Cadets, it’s unclear whether he had re-enrolled in college to continue this program.

It’s unclear whether Lena is a pacifist or simply thinks poorly of her son.

Perhaps Lena simply didn’t want her son to go off and die in a war, especially one that seemed to have nothing to do with America’s concerns. Meanwhile, it strikes me as strange that David is describing this whole situation as if from some distant vantage point. It’s as if he’s regarding two fools, his eldest son and his wife, arguing over the issue.

I wonder if we should see Al’s patriotism as a sign of Jewish integration into the U.S., as compared to how Jews viewed the military in Russia, with Ben Zion’s army experience when David was a baby?

Ah, this might explain Lena’s reaction, too, calling him a “fool” for enlisting in the army.

I don’t think the U.S. entered the war until somewhat later...

We didn’t officially enter until April 1917 but the Lusitania was sunk in 1915 and the "Preparedness" movement argued that the States needed to immediately build up naval and land forces for defense, assuming that America would go to war sooner or later.

This is where Albert has finally won the esteem of his father. David’s tone conveys a sense of pride, as well as relief.

On June 21st, Lena and Belle went to Rochester’s Mayo Clinic for medical observation. Next day David received a telegram from Mount Zion hospital in San Francisco that his sister Rose, the nurse, had died, having contracted typhoid fever while on a case.

November 6, a veil of mist covered the sky, a nasty folded veil so fine-meshed that it made one density. It was not exactly raining, but here and there the mist condensed on the surface into dampness, moistening the street, and made the pavement greasy and slippery.

David looked peevishly at a telegram just handed to him from Cincinnati, Ohio, saying that his long-lost brother Joseph was now recuperating in the city hospital from a serious illness, which he contracted while at the war front with the Canadian forces. He was now ready to be discharged from the hospital but had no place to go. So David wired a ticket and expense money to come at once and make his home with him.

Brother Joseph arrived very poor and dreadful looking. There was a sad and dramatic scene when his aged father met his youngest offspring Joseph, who had drifted about the world for [many] years without any paternal guidance or training. One who had rubbed his shoulders with people of the wrong class of society, now he stood, an emaciated, haggard, disappointed-looking youth. He stood with downcast eyes.

A heavy heart weighed on Ben-Zion. When he looked up he was startled to find that such a seedy young man was standing before him. Tears trickled down from Father Ben-Zion’s furrowed cheeks and dim eyes. To think of his wife’s stubbornness, all through life carrying a chip on her shoulder because she was Yanke Hennes’ daughter. Now their youngest child, a man of 32, who should be in the prime of life, [stood] before him a human wreck, without any religious training, with no respectable trade or profession to support himself decently.

Albert came home on a furlough on December 12th. He told David, “I wish I could join the Masonic Order.” He had observed while in camp that shoe boys who belonged to the order were receiving some better consideration from their officers. So David filled out an application for him. He received his apprentice degree on December 20, 1917.

(When Albert came home in April the next year, David made an application for his Fellowcraft degree, which was conferred on him by special dispensation by Master Walter Forbes. Three days later he got his Master Mason degree in the presence of Ben Marienhoff and a host of young friends. Albert was proud, especially when his sweetheart Ruth Mark presented him with a Masonic emblematic gold ring.)

The intense military officers’ training camp at Camp Custer, especially the practice with bare bayonets, had the purpose of creating a hard, sadistic yearning to plunge the blade into somebody’s bowels and to give it a twist. It was designed to inspire hate for one’s fellowman.

The trouble with most American boys was that they were brought up and trained in all kinds of special sports, but stabbing and cutting were difficult for them to learn with any conviction, as were knifing other men’s intestines and gouging eyes and various other animal combats. But such brutal training had sadly infected many of our returned soldier boys. It hardened their hearts and consciences to their home life. Later they took to racketeering and other agitation, and violence became rampant.

It’s unclear whether one or both Lena and Belle were examined. They had both been ill recently — if not constantly.

He is trying to be poetic but this is just awful.

Oh, I love it. It’s practically tangible!

It’s interesting that David has not mentioned that Joseph has been “lost” for several years. To this day his life between 1888, when David last mentions him, and 1917 are a mystery, although we can assume he remained with Leah until his teens (say, 1905).

David appears to reside at the top of a family pyramid, as the most competent and most successful one when compared to his father, his siblings, or his eldest son Al. Here we learn the sad fate of David’s brother Joseph, who ends up broke and wasted, without funds or a profession or any way to support himself or a family. We never learn why Joseph met such a sad fate — again leaving us wondering what special “magic” did David have that enabled him to flourish, when so many others failed to do so. The story also corrects our false impressions (based upon our admiration of David) that every immigrant found happiness and success in the United States. Perhaps there were certain personality types that did particularly well in this country, while others fell by the wayside.

Why is Ben-Zion blaming the problems with Joseph on his wife? Is this a misogynist pattern that Ben-Zion and David share, that they blame their wives for problems with their kids? Where has Ben-Zion been while Joseph was drifting?

By the way, we might tap in here to a theme in the work of Jacob Katz, a very prominent historian of European Jewry, who argued that Jewish economic upward mobility took place because families (in the middle ages and early modern era) did NOT help out the sinking sections of their families.

Is it just me, or is there no acknowledgment of Joseph’s service on the battle front? Is it not at all respectable that he has been a soldier?

David was a longtime member of the Masons.

This is important. The Freemasons were a crucial institution for assimilating Jews, going back to 18th century Germany .

David was aware that actually at least one of the reasons that Art went to Chicago (and elsewhere) was to evade the draft. We will find out what Al thought of this but would David have seen that as a good thing, Art’s avoiding becoming a bloodthirsty thug, or as a shirking of moral duty?

I have the feeling David would have considered it as shiftlessness or laziness on Art’s part more than anything else. He doesn’t seem to have esteemed Art highly enough to believe that he could be driven by any philosophical stance. Which, of course, he was.

In this and other places in the Diary, David’s lively description of current events doesn’t merely provide a context for his saga, but gives readers a glimpse of the times: America on the cusp of the Roaring 20’s. It seems to me as if David was writing with a sense of audience. And finally, here we are.