Year 1918

New Year’s Day, a raw, sunny and misty day. In the evening the family went to Mr. and Mrs. Mark’s home to offer condolences on the loss of their soldier son Milton, who died aboard ship en route to France under an operation. Albert called up, saying that he was to leave for the officer’s training camp January 4th. When Albert left in the morning for his camp, David gave him $25 expense money.

January 7. Lena was crabby all day. Grandma Calmenson came and had supper. They received a call from sister Freda that mother Leah was very sick and went in the evening to Minneapolis to see her. David sat there in the dark, giving her comfort just by being near her. She watched him through her slitted eyelids. She tried to whip up some desire or even some pity for him. Her mind responded but her blood lay chilled beneath her flesh. But even thinking about his psychology, there was no practical proof in that [which] she must think about now. It was to lift herself over things with it, for there was no doubt in her mind to go with that. Well, certainly not unless she could get back to where they had always been before this terrible thing came up.

I have to assume David is talking about Leah’s contemplation of her death, but it’s pretty muddled!

While at dinner on January 16th, Helen showed an engagement ring from her friend Moshe Rosen. Lena began dictating terms to David and blamed him for the whole affair of which he knew nothing at all. Lena said, “Why was it done in this mysterious way? I don’t like mysteries in my home.”

Helen replied, “Young people are always mysterious over such things.” Lena replied, “Thunderclouds shall not burst under my roof.” She shrugged her shoulders as if ferreting out the reason. If any act was needless waste of energy and said, “You got the hell fired pride that won’t give down when you see them with your own eyes and know in your heart what convicts you.”

February 19th was terribly cold, 30 degrees below, with a strong wind blowing. Lena had been sick for the past three days, since Helen told her about her engagement. David felt miserable and had to go to bed. The pain stabbed his back as if a hand would hit his heart.

Now Helen is engaged to Moshe Rosen, and neither parent likes him? But they didn’t like Art Singer either, right?

Do they dislike Rosen, or just the “underhanded” way their engagement has transpired (that is, Helen has been deceitful and autonomous)?

This is one of several places in the diary where David’s phrasing/narrative becomes, frankly, incoherent. I have noticed that these instances all seem to involve emotional climaxes of some sort — either David feeling on the brink of despair (often followed by his resorting to an equally bewildering spate of philosophy), or Lena’s frustrations suddenly erupting and being transcribed (questionably) by David.

February 27th. A very cold winter night, so silent that the moon congealed to the stillness of the glass, spread over the city; ponds and ditches were frozen hard. The puddles made glazed eyes in the road. On the pavement the frost had raised slippery knobs. Darkness pressed on the window; no light shone, save a searchlight rayed around the sky and stopped here and there. Lena was feeling worse; Dr. Campbell attended her and left a prescription for her.

And yet it’s immediately followed by this brief but beautifully clear and poetic passage!

On March 11th, Lena took sick with a bad spell. She groaned; her forehead and temples were pinched with neuralgia; tendons jerked liked cords in her throat, and the color in her cheeks looked as if it had been burned by the flame, but her contours, the perfect oval of her face, had resisted time and sickness. A horrible misgiving now took possession of David, a feeling of positively physical pain situated in the pit of his stomach. But he bore it bravely. Belle went with him to Dr. Allen for a thorough physical examination, but there was nothing wrong with David.

April 9. Grand spring morning, spraying the street with a misty radiance while the brisk breeze, which had thrown the fleecy packed clouds from off the pathway of the sun, now moved the rays slowly onward in a glow of golden haze. In the evening David attended Master Mason's work [sic].

Just what do we make of this marriage? Is he ever sympathetic to her, does he think she is a neurotic whiner, or what?

This is a weird passage because it almost seems as if David is seeing Lena in a new light (“the perfect oval of her face... had resisted time and sickness”) and that he is momentarily struck with a sense of guilt or fear that he might lose her. But then he shifts gears, tying his “horrible misgivings” to his own ailment, as if to say, I’m succumbing to empathy and it’s made me ill. He goes to the doctor and discovers that he’s just fine.

June 2. At breakfast Helen told an exciting story of how policemen Guy and Johnson beat up three foreigners for, as far as she could determine, no apparent reason. It was an inhuman beating, she said, and entirely uncalled for.

June 10. David received a letter from Albert announcing his commission as first lieutenant. David forbade Helen to take out the car and she retorted, “I’ll blow up the darn car if I’m not allowed to drive." That was the only thing she came home for.

June 18. South St. Paul primary election day. Abe and Belle left for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as St. Paul delegates to the Hadassa and Zionist convention. Helen went hiking.

On June 19th Miss Ruth Mark received a letter from Al complaining of his hard camp life and the poor accommodations at the training camp. Lena began fretting over it. Also, the letter said Albert was promoted to first lieutenant and asking for $200 for an officer’s outfit, and a pair of military puttees, which David sent to him.

Troubles with Helen

Later, Helen said to her mother, “I have some confidential words to tell you. Something frightful to say. I want your advice.” “What is it,” her mother asked. “Moshe loves me no more,” she blurted out, “and our engagement is off.”

Helen certainly had a hair-trigger temper and a talent for getting mixed up with curious crowds. David thought for a moment, and Lena listened silently. She was not swept away by her daughter’s story. She did not weep over it, but panted for breath, her hands clasping each other. Her eyes filled with emotion. She stared at Helen, then mustering up courage she said, “Well, it is past.” Then she added: “No use crying over spilled milk. You must rid yourself of sentimentalities. You are free to master the art of living, which is the only reward of character. It is a matter of self-planning and self-control.”

There are a few glimpses of Helen as a thinking, sensitive, good person, and this is one of them. These bits of evidence are all I’ve got in Helen’s favor, aside from a very few stories my mother has told me and my own dim memories.

My mother contends that her mother never learned to drive and never wanted to, one of her many “limitations.” Well, she certainly seems interested enough in driving here!

How rich do they have to be to own a car at this point? This is actually kind of contemporary!

Here is one telling example of the difference between the sisters, told with unintentional deadpan humor: “Helen went hiking.”

Abe and Belle involved in Zionism: I wonder whether this was an ideology or a social set that made David happy, which perhaps none of his other kids shared.

Hearing those words from Lena, David murmured, “I see our children are far from geniuses. True, they may have fair ability.” Helen decided to meet Arthur Singer, and Moshe Rosen was her accomplice.

On July 1st, David received a letter from Albert that he was about to be transferred to some other camp, but he didn’t know where. He also received a letter from Helen in Trenton, New Jersey, that she was sick, and he sent her money to come home. Lena had received a letter from Eva [Wilk, her niece], saying that Helen had complained to her that her parents were abusing her at home, that she did not want to be bossed by her mother, and adding that much money was spent on all the other children but not on her.

Is David criticizing Helen and Lena, or just Lena? What’s the connection between genius and the failed engagement?

“Meet”: that is, at this point Helen decided to seriously pursue Arthur, who had at that point gone to Trenton.

Yes. My mother says that Moshe basically fixed them up. Moshe was Art’s good friend for years and years, into my mother’s youth. She relates that he was, like Grandpa Art, outgoing and a flashy dresser.

Is David owning up here to his daughter’s critique?

On July 4th, a sudden burst of July sunshine penetrated the dark veil hung by the last drops of the passing drenching rain. Lena was all excited about Helen’s whereabouts. At 10 a.m. came a special delivery letter from Helen stating that she was in Fargo, North Dakota. [But] two days later, Lena intercepted a letter for Helen and opened it and discovered a supposed clue that she was to go to Arthur Singer, who was expecting her to come to Trenton. Lena went to Minneapolis to find out from Moshe Rosen, who told them that he was under the impression as well that she had gone to Arthur. Lena was raving mad all night. She fainted at 6 a.m., and David had to send for Dr. Campbell.

All day her brain walked around the subject and looked at it from every side. Sometimes she had to hold her poor shivering brain by the scruff of its neck and make it look straight at the problem.

July 7. Cool and cloudy. Lena called up her brother Philip Laser [who had settled] in Chicago, telling him about Helen. Later she and David drove to Bald Eagle [a lakeside community north of St. Paul] and discussed the matter with Abe and Belle. Belle wrote two letters of inquiry, one to Miss Morell, and one to Miss Sprague, Superintendent of the West Side Neighborhood House, where Helen had taught a class one day a week, on the supposition that they knew of Helen’s whereabouts.

July 12. Helen came home raving mad, but not explaining her return. Helen packed a grip full of clothes and many other things and, assisted by Moshe Rosen, left the house to go to Arthur Singer. When Lena heard of it after she came home, she fainted when she found Helen’s note on the dresser. David felt as if the earth was caving in and the bleak waters were coming from the depths and rising up and the hills crashing.

So... she had left Trenton for Fargo, and now is back to Trenton? Or she was lying about Fargo? Or is the timing off in the telling?

Helen was clearly up to something here. There can be little doubt that she was attempting to conceal her actions from her parents, whose support, such as it ever was, she not only didn’t want, but wished to avoid. And why not? They had failed to recognize any talent or strength in her, or to respect any of her accomplishments (for instance, teaching in the Neighborhood House, in itself an act of social conscience). Helen was doing what she could to take control of her own life at this point, and she had obviously decided that Arthur was going to be a part of it. She was done asking for her parents’ advice or consent.

I love this. I’d like to think that David had a sense of humor about the whole Helen situation and that this is an expression of that, but I think it’s safe to say that he was just an unschooled writer trying to describe his wife’s agitation.

Are the two parents on the same page re Helen’s escapades or are they fighting about her?

I think it’s another instance of David’s detaching himself, wherever possible, from the fool’s parade of his family (i.e., the antics of Lena, Helen, or Albert), reporting events from a safe remove.

On July 15th, Helen wrote that she was working in Trenton, New Jersey. David received a letter from Albert that he expected to be transferred at short notice but didn’t know where to, and received letter from Miss Sprague, reprimanding David and Lena in blackmail style, accusing them of neglecting financial support to develop Helen’s intellectual career and give her an opportunity to study for the stage. A mother’s instinct is one of the deepest and most powerful of human instincts, and while it wasn’t always rational, it was, when aroused, invariably pugnacious. David knew that that period was just as trying for Lena as it was for him, though at the same time he became unusually irritated at her. At the bottom, however, he felt genuine sorrow for her. “You are a good enough woman,” David said, “but too fond and foolish, Mother. There is more love in your heart than sense in your head.”

The first tidal wave had broken. David now wanted the subject dismissed. He had lived with this problem, eaten it, dreamed it, walked the floor with it, and cursed it. “There are laws everywhere,” he said. “We cannot live without laws. Laws of nature, laws of God, and laws of men. Until we learn to obey them we must go carefully and take advice from older hands. The mush-head did not believe. Are you one of those [who are] proclaiming liberal thoughts?”

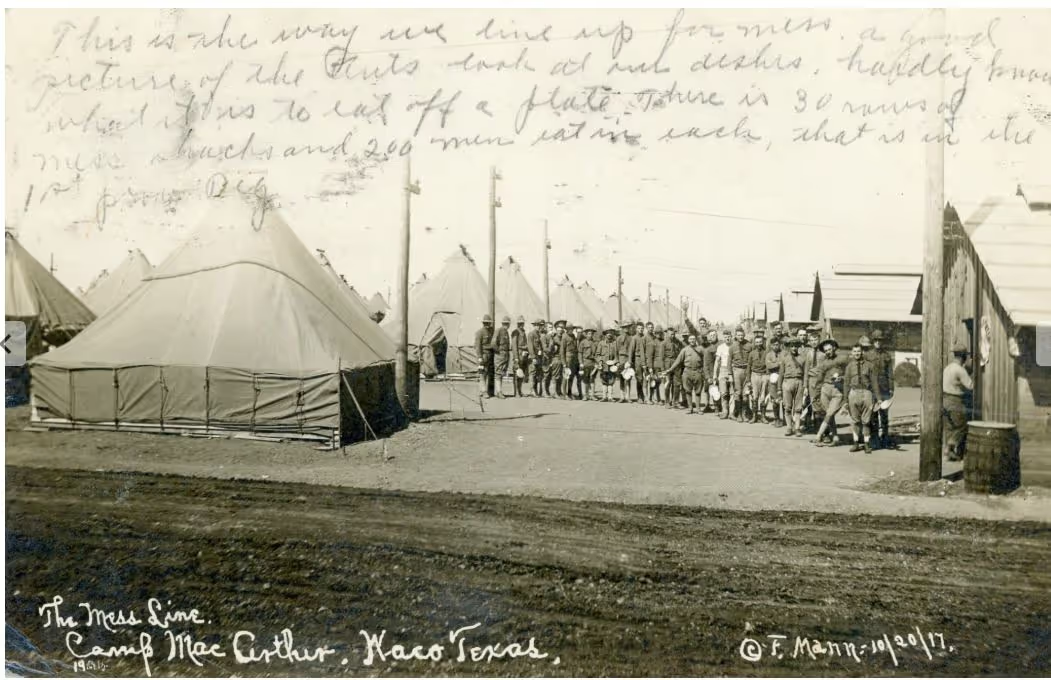

July 19. David received a wire from Albert that he was to be transferred to Waco, Texas.

July 23. All factory whistles blew for 15 minutes in long blasts proclaiming Allies’ victory over the Central armies, but later it was announced as false and premature.

August 3. A very hot, close, and humid day. David was disappointed with continued car trouble all day. David admonished Albert in a letter not to be hasty in getting married and to wait until the war was over and he was back home safe and sound. David left for Chicago on a business trip.

Another nugget of evidence that my grandmother had a mind, as well as a serious, sustained interest in theater or dance. Miss Sprague sounds like the first, if only, mentor my grandmother ever had, in the sense that she esteemed and advocated for her. I have to wonder: if Helen had had the means to pursue her interests, would she have married Arthur? At any rate, I feel sure that she would not have returned to her family home after breaking away, no matter what, but I also suspect that on some level, she married Arthur as her safe ticket out of there. How many options were open to women then? Not many. In lieu of theater school, marrying an upbeat, open-minded, handsome man that she loved was a great second option. We’ll never know if that was Helen’s reasoning or not.

As for David, he seems to have little love in his own heart and not much more sense in his head, despite his protestations. He is at once calling his daughter a mush-head and yet also telling Lena to get over it! But I’m not sure what he’s getting at below with “liberal thoughts”: is he talking about liberal religious views? And is he accusing Lena of this? She doesn’t come off sounding particularly liberal here.

He’s just said that Lena has “more love than sense,” so perhaps Lena actually struggled with feeling that they should offer Helen help (fund her schooling?), or make some other sort of conciliatory move.

August 9. David arrived home from Chicago and found a letter notifying him of an injury suit pending on account of Helen having run over a girl on the 20th of May, carnival week, in South St. Paul. “I think,” David murmured, “you cannot improve silly people when they get obstinate if they cannot understand and you cannot make them understand. It cannot be helped. I always sympathize with their position.”

Perhaps this explains Helen’s later reluctance to drive!

Helen appears to have returned at least temporarily from Trenton...

Wednesday, September 11. Gloomy, nasty, and drizzly day. David was in the store at 9 p.m. when young Acklund with Mr. Moe, foreman of the tannery, came into the store. While waiting for Acklund, Moe snatched one pair of pants, and tucked it under his coat. Coming towards him, David disregarded his request to look at a shirt and calmly unbuttoned [Moe’s] coat and pulled out the pants. He called for a policeman. When officers Guy and Johnson responded and David learned who Moe was, he dropped the affair for the sake of Moe's family.

So who was Mr. Moe, and why does David do this?

Why drop the case? Good question. Politically expedient?

Friday, September 13. Lena started a rumpus about Helen and Arthur using crude words and cursing. David told her that if it was her desire he’d make an end to the whole outfit, but she didn’t want him to do anything. Later all went to a movie.

On October 16th, David received a letter from Albert informing him of his coming home, intending to get married within four weeks. Great northern prairie fire still raging; 1,200 people reported dead, 4,500 homeless. Solicitations of donations for cash and clothing for the unfortunate at high pressure speed by all the newspapers.

David replied to Albert, admonishing him not to be in a hurry to get married. He should better wait until the war is over and see what he can do to make a living for himself and a wife. When one embarks on the sea of matrimony he should not jump overboard if the squalls, storms and waves are higher than perhaps expected.

October 20. Received word from Albert that he received notice that his regiment was to sail for France about November 15. Albert’s sweetheart, Miss Ruth Mark, insisted on becoming a war-bride, which was all the rage. Albert was granted a furlough of 20 days to go home. Thus, he would be back in time to report to his company.

Two terrific words here, “rumpus” and “outfit”: the first makes sense but what does the second word mean?

Apparently Helen and Art are back in town, but is Helen back living at home?

Good questions. Does he mean “put an end to Helen and Arthur’s relationship”?

October 25. David received a letter from Albert reprimanding him for not consenting to his marriage before going to war. He accused Belle of opposing his marriage.

November 1. David went to Minneapolis in the morning. When he came home Lena told him that Ruth Mark had told her that if Albert didn’t come home to marry her, she would go to him and be married there. On November 4th, Albert arrived from Camp [Mac]Arthur, Texas. Ruth Mark had dinner with the family. Later, Lena went to Minneapolis to see her sick mother, who was rather low.

I think that Belle is definitely over-empowered as a daughter, functioning like David’s wife and a third parent to the other kids.

I concur!

November 7. Heavy rain continued from last night. A false alarm regarding a signed peace report by the Germans and their allies electrified all the United States. Factory whistles were blowing and church bells tolling. In the evening we took a taxi and went to the Marks to the reception. We came back in a heavy storm. Issuance of a marriage license to Albert Blumenfeld and Ruth Mark was announced in the daily press.

Sunday, November 10th was a grand day, Albert’s wedding day. David and Lena left home at 3 p.m. with Abe and Belle in the family car. After the wedding Albert and Ruth were driven to the depot at 8 p.m., as he had to be in Waco by the 15th. All had a nice time, and David and family came home at 11 p.m.

One of the few lapses where David uses “we.” This was the kind of stylistic clue (apart from a plethora of clear facts) that finally convinced me this was not fiction.

The honeymoon of their marriage passed in a glow of warmth and joyous discovery beyond any power of words to set down. There was never in the glittering realm a sound of joy like this.

On the very next day, Monday, November 11th, before dawn, wireless messages announced to the world [that] an Armistice was signed in the presence of General Pershing, Marshal Foch, and many other notables and military dignitaries. There was great joy everywhere over the ending of the greatest war in history. There was celebration all over America. Factory whistles screeched, church bells tolled; at 8 a.m. the Swift and Company and the stockyards employees laid down their tools and began celebrating. David and his family went out riding. Later they called on the Calmensons and had supper there.

The mobbing, the pelting of roses, the kisses from suppressed, hot-lipped women who were perfectly respectable. The little flasks of whisky and cognac from many good-natured men’s pockets. Wavy lines of factory girls arm in arm, some of them half drunk, swayed along amidst the crowd, jostling men and squealing pert coquetries. There hovered about sundry lecherous looking males, much attracted by this throwing down of the outer earthworks of sex. Arms were thrown around strange necks in tight embraces. Girls shrieked endearments or words of immodesty or abuse like cats at their amorous cries on roofs. Men fanned their erotic fires with jests and buffoonery.

An unmanageable excitement took over the nation. With uplifted arms all began to shout, “The war is over! The war is over!” while thousands laughed and wept. A combination of tumults. What joy or heartbreak was in their cry, God only knew. People were shouting that the boys got the Kaiser and crowds laughed, for a man moved into the light carrying a scarecrow on a long stick and yelling, “Here, here, we got the Kaiser.” The war was ended as suddenly as it began.

So what’s the “glittering realm?” Is David happy for himself as a father, or for them?

In any case, this is another example of David’s fluctuation between extreme romanticism and bitterness.

I think David’s natural condition of wonder, exaltation, at nature, for example, the impulse that compels him to write, is always in fierce battle with the pragmatics of dealing with poverty and other strife. As in his own marriage, which was based on love at first sight and disintegrated shortly thereafter as reality hit, he will soon bemoan Al And Ruth’s ill-thought-out union as though Youth has not learned from the Elders; or perhaps it is another of those inescapable laws he feels weighing down humankind.

This is another one of those great panoramic descriptions of David’s. Sure, the phrasing is awkward or outdated in places, but to me that’s what makes it genuine. He captures just enough of the specific sensory details to bring the occasion alive.

Coming home from the wedding Lena had taken sick suddenly. David sent for Dr. Allen, who pronounced her case a heavy flu which was then so much raging. Two days after Albert’s wedding David received a telegram from Helen in Trenton, New Jersey stating that she was married to Arthur Singer and that Moshe Rosen acted as best man and witness for them.

How frail is health, and what a thin envelope is it that protects life against being swallowed up from without or disorganized from within. A mere breath and the boat springs a leak and founders. A nothing, and all is endangered. A passing cloud and all is darkness. Life is indeed a flower which the heat of a passing wind may break down.

David had gone around as though the very heart had been shot out of his breast. He was doing his utmost not to let his worries achieve mastery over him. He was deliberately schooling himself to keep his attention focused on extra household topics, but try as he might the shadow of it could not escape. David was angry but he did not know why. He had not the faintest idea why. But he soon realized that anger is no sort of weapon with which to fight solitude.

November 14, Belle took sick. Dr. Allen diagnosed her case as a severe flu. Three days later Belle’s sickness took a turn for the worse and she fainted. She became frightened, and Dr. Allen ordered her to St. Luke’s Hospital. Mr. and Mrs. Calmenson happened to come in just as Belle was taken to the hospital. So Lena, Abe and his parents went along in the same car to the hospital. The following night Abe took sick. As soon as Belle felt somewhat better and able to move about, the Weilers took her to their home for recuperation.

November 18. David received a letter from Helen asking for some things. Lena went to town and bought a supply of linen bedding and many other things for her. Also Mose bought some silverware for her gift, and they expressed it to Arthur Singer in Trenton, New Jersey. On November 19th, Abe reported that Belle was resting a bit easier. David received a letter from Albert that he and Ruth had arrived safely in Waco, Texas and fitted themselves in an apartment.

Helen marries Arthur quietly (elopes, actually), an interesting counterpoint to Al’s respectable nuptials and all the blessings he tried to secure from his father beforehand. Helen had to have known how much this would irk her parents. I would have loved to interview my grandmother about what was going through her mind and how it all seemed to her — the Great War ending, her decision to marry without her parents’ knowledge. What I can say is that I think it took considerable courage and initiative for her to marry Arthur the way she did and try to set out on adult life on her own terms. She was doing all that she had it within her limited power to do.

David seems to have realized that, on top of his ongoing estrangement from his wife, in the space of a month he has lost both a son and daughter to marriage. He seems here to evince the closeness to Helen that my mother thinks was there despite the many passages of impatience in the Diary.

I assume this means a medical operation, not a military exercise.