Years 1913-1914

Belle came home sick from the New Year’s Zionist Ball and was taken to the Weilers’ home for recuperation. January 3rd, Albert took sick with a 103½ fever, suffering intense pain all day and night.

February 14, the Jewish Encyclopedia set of books arrived...

February 20: On a telephone call from [Lena’s sister] Mary Bank, David went to Minneapolis to call on Uncle Laas at the Swedish Hospital. He found Aunty Laas sick at her home. Coming home, he found Mose sick, with symptoms of measles.

May 1, the day was clear and golden, transparent so that the skyline swept out an immeasurable distance. The softened light flooded the city and the quiet air was a real gaiety. David went to Stillwater on business in the morning. Came home very sick. While he was convalescing Lena and Belle had a wordy altercation almost reaching to blows for Belle’s meanness in not letting Helen have one of her three white dresses for her school play. Helen had to run all over town to look for a dress. Finally she got one from Margaret Lewis, Dr. Lewis’ daughter.

On May 26, Abe Calmenson and Belle’s engagement was announced in the local paper.

This constitutes a rare “defense” of Helen, on the part of both David and Lena. It is the only shadow that crosses Belle’s character throughout the diary.

Deborah: This must have been a huge achievement for the family. Do we know any statistics about Jewish proportion of lawyers graduating/practicing at that time?

On June 4th David closed the Rice Street store and brought all the merchandise to the South St. Paul store. On June 13th it rained hard in the morning. Belle, Eva Zalk [Lena’s niece], and David went to the College of Law to see Abe Calmenson’s commencement exercises, at which Abe graduated with honorable mention.

June 15th was a very hot and close day. Ben and Morris came in the evening. There was a time when the children played under the piano. Another time when they rolled back the rug for dancing. But after Belle’s marriage the room would always be orderly. It was saturated with comfort, the walls bright with the color of life.

June 20th was a fine morning. Lena got up early preparing a full lunch basket for the I.O.B.B. [International Order of B’nai B’rith] boat excursion to Gray Cloud Island . The party consisted of Abe and Belle, the Weilers, and several other friends. There were many games – basketball, footraces, baseball, and a nail-driving contest. Lena joined in the last named game and came out the champion nail driver. She felt proud over it.

Coming home from the excursion the steamer hit a low spot, an uncharted sandbar, and Lena was worried about the delay. The band played while the crew worked to extricate the steamer from the sandbar. Henry Weiler said to Lena, “Don’t worry. You’ll be home on time to set your biscuits in the oven.” All had a hearty laugh over it. But Albert and Lena didn’t enjoy the excursion. They both came home sick for some reason. The doctor had to come twice on that day. Next day they were safely out of danger.

We never learn what happened with the Rice Street store — why did it close so quickly? David is not so forthcoming about his failures in business now, and he only wants to tell about his successes. I want to admire him, I want to model myself on him, but there seems such arrogance in him at times. He is so quick to find fault with so many around him, taking full credit for his success and attributing it to his better character and inner strength. And compared to most everyone around him he was the star of the family — in terms of wealth, productivity, and civic contributions. But why does his pride in his own achievements morph unpleasantly into harsh judgment of those around him?

My read is that he bought out someone else’s store, kept the stock, and then sold the property.

Life is a bundle of contraptions, David mused, and the skeptic has to welcome them all. He has to wed pity of imagination to sympathy of thought and common-placedly permit reverses to jostle in her track.

Soon after Abe’s graduation from law school, Lena began planning for Belle’s wedding. Lena was a bearcat with her skillet-made meats submerged in delicious sauces. Vegetables disguised by art so that one could only guess at the originals; cakes whose being was little short of a miracle, and pastries of a light crispness which amazed the eye and astounded the palate. David’s clerk Frank, who was quite an artist, decorated the ceiling and hanging lamp beautifully for the occasion. They procured a large Victrola with many select records for the event.

July 1st was Abe and Belle’s wedding day. A grand charivari [a group serenade] was led by Clyde Whitman and Fred Schultz. All the horsemen of the yards surrounded the house with their usual Indian whoopee until they were given money for drinks and departed with pistol shots and happy Indian yells. In the evening many friends came to the reception and had a great time.

But the groom’s mother, Mrs. Calmenson, acted much displeased and disgruntled at the omission of some minor traditional ceremony. Although the groom had trampled and broken the customary glass with his foot, his mother was still nursing a sour grapes philosophy to the extent of not partaking of the very nice supper, which Lena had prepared, and Lena felt peeved over such narrow-minded notions of Mrs. Calmenson.

On July 11th David came home from a week’s marketing in Chicago and Milwaukee, and found Lena and Mose sick and called for the doctor. He closed the contract for a new storefront for $540 . David’s heart was full of bitterness. He felt distressed when Lena told him that she did not feel any better. He bit his lips and trembled from irritation.It is said that emotion is like alcohol in that it stimulates the animal mind and appetite without exercising any positive effect upon the intelligence and social action.

On August 19th Lena left for Mud Baden to take a course of mud baths. Abe and Belle came in from White Bear to stay in the family home during her absence.

More muddled philosophizing, but I think what David is on about here is an admonition to take the bad with the good, an idea he comes back to later.

Does he mean contraptions or contradictions?

Lots of fun history re: the charivari. It was often lewd and noisy — I didn’t know that Jews did them too. Actually these two names don’t sound Jewish, which is in itself quite interesting.

Now, this is an interesting image for a Jewish wedding! I wonder whether Ben-Zion was there and what he would have made of it.

I am used to thinking of Native Americans in contemporary Northwest rodeos but hadn’t considered they’d be cowboys in the Midwest as well.

When I read this, I envisioned the horsemen as white “cowpunchers” imitating “Indian whoopee” antics.

Fascinating to see how the women have a conflict over how “Jewish” their children’s wedding ceremony should be. This shows that the rabbis were not the arbiters of religious ritual, but members of their communities who have their own strong opinions about ritual observance and are used to fighting about these things. So Lena is the open minded modernist here....

Does he not believe that she is really ill? Why is he always so vexed about her?

If this is the maxim he uses to try to control his life, he really wasn’t very hip in the terms of the day, probably he would never have heard of Freud. But you would think that if he had read any modern novels such as Tolstoy or Flaubert, and thought of himself as a writer, that he would have a more sophisticated sense of the emotions. Do we actually have any idea what David was reading? I would be curious to see the Yiddish readership of the classic adultery novels of the nineteenth century such as Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary, or even writers in Yiddish such as Shalom Aleichem and Y.L. Peretz.

David, Albert, and Lena

On September 6th Lena came home from Mud Baden and brought two girls along. David was very ill, nursing his painful toothache. David thought there was something absolutely wrong with Albert and he felt sad over it. As a youth, David thought to himself, he [himself] was deprived of an opportunity to mingle with others, as his father had apprenticed him at the age of ten to a tailor to learn a trade. He thought a youth should spend his time in eager curiosity though he need not formulate his purpose. A youth should be tossed out without much reservation and cut out his own career. David felt there was nothing the matter with Albert except that he had a “pain in his neck” and seemed to need a good trouncing on his jaws more than anything else.

Lena [was] feeling weak and unhappy, and acted very indignant and began to talk about Albert studying medicine. David reasoned, “There is no use. He has no mind for study. You can lead a horse to the water but you cannot make him drink if he doesn’t want to.”

David saw the color stealing into his wife’s cheeks and at the same time a freezing sensation traveled down through her body when he told her of Albert’s scholastic record. In order to convince himself David had gone to the University Registrar’s Office for a correct statement of Albert’s standing and credits. He was told that Albert would have to make up a new course in order to keep up his grades.

One morning Lena was shaking a small rug at the head of the stairs when she lost her balance and slipped on the banister, spraining her ankle. The doctor examined her and told her that it was not serious. “She needs rest for several days,” he said. And he told her she had symptoms of gall bladder disturbance. Lena began raising a rumpus because the doctor told her that her liver didn’t function as it ought to. He told her bluntly that there was nothing wrong otherwise with her heart, lungs, or kidneys.

“Take those pills,” the doctor said, “and you’ll soon feel better. And don’t imagine any serious disease but tend to this only.”

Lena told the doctor that she feared the neuritis had become complicated with heartburn. But the doctor said, “Forget it. Don’t brood over it.”

What I hear David saying here is that in looking at Albert, he thinks back to his own youth and all the deprivations he endured. He did not have Albert’s opportunities to make friends or pursue intellectual interests. Yet despite Albert’s privileges, the youth is basically a dud. David comes across as both envious and resentful of his son; if he had had the opportunity to go to college, he would have made a success of himself!

David’s pronouns get cloudy here but I believe he’s saying it’s his father who thought “a youth should be tossed out.”

Again we struggle to figure out what is the real source of Al’s problems. David tells us he lacks curiosity, he has no mind for study, and he won’t be a success. I muse about how my mother’s life would have been different had Al pursued a profession instead of running the family store for so many decades; would they have been richer, happier, more prominent? Why was the younger son able to climb so high on the social ladder, attending Harvard Law School and becoming a prominent judge, while Al fell to the side, not able to move beyond his father’s world? Indeed, Al never even achieved the social position of David, nor did he pursue any of David’s intellectual interests.

So David has no sympathy for Al whatsoever, how is that different from his hostility to Helen? And to his wife?

So basically he and the doctor both think that Lena is a hypochondriac? There is a lot of historical writing about well-to-do women in the 19th century who had “neurasthenia,” which was a kind of hysterical lassitude. What is interesting is that Leah had been a business wife and so had Lena at earlier times when the family was poorer.

One of Helen’s characteristics that my father always drew attention to was what he called her hypochondria. Of course, his own Uncle Clyde was past master of that art. But Lena seems to be full of similar fears.

Fear causes perhaps more unhappiness than any other thing that we let take possession of us. Some are never free from it. They awake in the morning with a vague indefinite sense of [fear], and it might be foreboding distaste bounding over the torment tremors . Life would have a different meaning if we would resolve and keep the resolution to do the best under all conditions and never fear results.

Lena was trying to control herself and prevent her trembling, determined to go through the ordeal as the doctor directed. “Now a human body will stand only as much as a human body and mind will conceive. But there is a limit to endurance,” she said.

In September Albert began to work for Swift & Company in their chemical company. He decided that he wanted to do experimental research work in chemistry in his spare moments. So a small laboratory was fitted up in the basement with a bench and a gasoline stove. He bought about $50 worth of glass utensils. When he began experimenting, his work emitted a terrible stench all over the house. But Lena did not grumble over it as she thought that her son was a born genius. But he soon got tired and dropped his experimental work, as he lost patience.

Year 1914

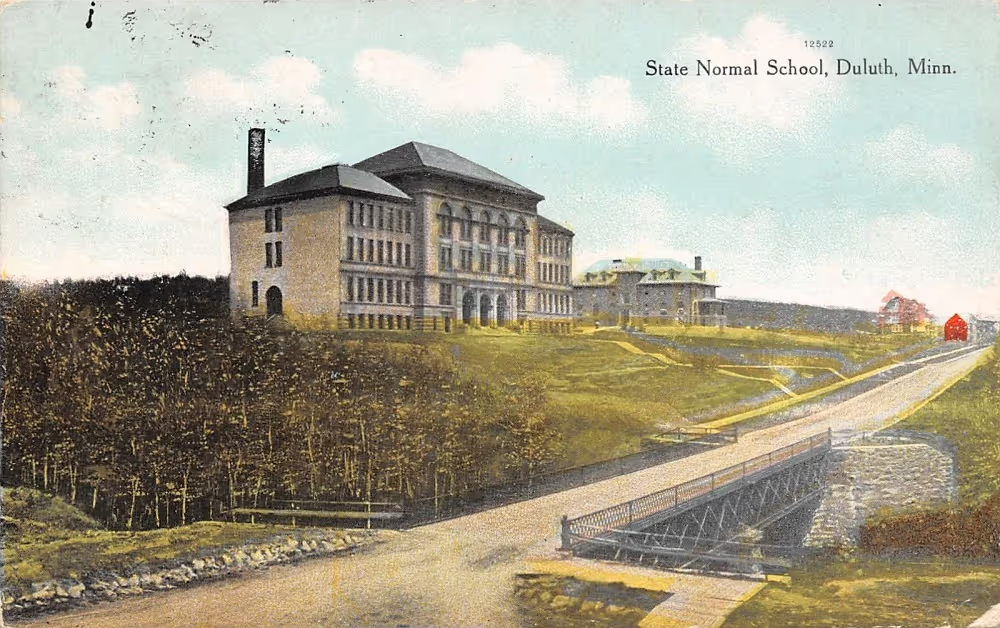

In June 1914 Albert was discharged from his job. David went to see the superintendent to ascertain the reason for his discharge. He was told that Albert had no spark of enthusiasm about his work. He had no personality of a pleasing type to make him grow into the company. He walked gloomily as usual. If he smiled no one saw him. He was of the unsmiling type. The lines of his mouth were like the jaws of a vise. So Albert decided to go to Chicago to work for the Morris Fertilizer Company. David had little faith in his change. He gave him expense money and [Albert] left. The entire family went to Helen’s high-school graduation. Later she was sent to Duluth Normal School for study .

These little aphoristic sections are curious. It seems almost as if David is writing them as reminders to himself; he’s telling himself to “do the best under all conditions and never fear results.” Yet, he doesn’t seem able to let go of his fears where his children are concerned, by letting them go and do their best, whether it’s Helen’s wanting (later in the Diary) to pursue a career in dance or Albert’s feeling ready to take on a role in the family business.

Has Al dropped out of the U? Is David giving him any credit now for getting to work? So Lena is soft on Al, is that one of the reasons why David hates Lena? Maybe she needs to compensate for his judgmental meanness to two of the four kids?

Helen, the second daughter, was an unruly kid. She was not only silly and cunning but spiteful as well. She was up to many pranks and poor at her school studies. Lena wanted her to become a pianist. The music teacher, after testing her out, said that she had an ear for music, provided she would practice. More than once Lena pulled Helen by her hair to make her practice at the piano. But Helen was up to many stunts. She was wild as a hare and loose as ashes, and at times did not hesitate to tell lies.

Helen’s face was a thundercloud and her eyes an electrical display. One could feel that her threats were no idle ones. She was a demon when roused. There was strong metal in that girl. You could not cross her slightest whim without courting trouble. She was as difficult as a ferocious colt, [self-]important and skittish. She would give an uncontrollable tongue lashing to anybody who dared to set up a similar proposition . Her comments about people were measurably “pricky.” She seemed peeved and had a small, sharp hostility to all mankind. Few cared for her behavior.

She played the piano fairly well. Later she got a job teaching in a school for subnormal children. But she was of a flighty disposition, imagining herself cut out for the stage, for acting and dancing. She had the nerve to tell her mother that she should not become anxious over her causing much grief with her illusions and misbehavior. She was sucking the vital goods of her father David’s soul. She had moods, she grew irritable and depressed. She could not hide the change from him. David said if a girl has any real charm and womanliness she would not have to look for a man; she’d find them lined up five deep at her doorstep.

Let me testify to the fact that ninety-five per cent of middle- and high-school students exhibit spates of silliness and episodes of wild haredom. It’s called being alive. And if Helen’s home life was punctuated by her father’s stony silences and mother’s alternate hair-pulling (yanking Helen to the piano) and groaning with pain from the bedroom, it is hardly a wonder that my grandmother felt the need to vent some pent-up energy and frustration.

Great phrase: “wild as a hare and loose as ashes.”

Now this comment is one that jibes with what my own mother, Helen’s daughter Beth, says. According to her, Helen had very few good things to say about anyone and was possessed of an unusually sharp tongue. My mother has furnished my imagination with many hurtful scenes from her childhood, and I do not doubt that my grandmother said some terrible things to her children and my grandfather. However, I never heard Helen say a negative word about anyone. Not once. She was a loving grandma to me, until she died when I was about 24 years old. So, I am left with the certainty that there was more to Grandma than my mother’s, and now David’s, narrative suggests.

The “subnormal children” moniker irks me no end. Perhaps it was the phraseology of the times, but nowadays, Helen would have been regarded as a teacher specializing in students with special educational needs. Even if this is how people referred to children with learning disabilities in those days, David’s tone suggests something more; he seems to imply that Helen is only equipped to work with children who are below the average, because she is also below par.

“sucking the vital goods of her father’s soul”: this is a most bizarre turn of phrase, no?

So [a] seed fell into the crooked furrows of his vacant brain in the candle-lit darkness of his mind, and an idea was born.

July 20, 1914 was a great day among St. Paul Jewry. The members of Temple of Aaron congregation and their friends gathered together at the laying of the cornerstone of their $60,000 synagogue building at the corner of Ashland and Grotto streets.

Lena’s sister, Mary Bank, was very sick. She was run down from overwork and undernourishment. Her husband, Samuel, was a slow-moving proposition, a helpless sort of man. He had little interest in his family’s well-being. Sister Mary was thin as a rail. Her face was all eyes, and in spite of the high color her skin looked waxen. She was weak. Her pain was intense. The pulse of her heart seemed suspended. A tremor had crawled up her spine and was spreading over every part of her body like millions of tiny, invisible creeping feet. When the doctor examined her he found that her lungs were badly affected with tuberculosis.

“An idea was born”? What idea? Frustrating vagueness. Is this perhaps an allusion to getting an idea for a novel?

Why haven’t David and Lena been helping Mary? There’s lots of discussion among historians about the competing goals of upward mobility versus helping poorer family members.

There were four children, three boys and the youngest, a girl four years old. She was a very weak child – weak from lack of care and undernourishment. So Lena took the girl to take care of her during her mother's absence at the Denver, Colorado sanatorium, and the three boys were left with their father and he was to look after them as best he could. Lena had a big heart. She was the most extraordinary combination of a perfect lady. To add to the unfortunate family’s grief, Samuel Bank was operated on for piles at the Eitel Hospital. His suffering was intense and his recuperation was rather slow and painful.

Mary came home from Denver after a long stay. Although she was much improved on her return, the poor home care, hard work, and lack of proper food soon resulted in a relapse and she then went downhill rapidly. She was taken to the Thomas Hospital in Minneapolis where she expired on October 14, 1914.

Ah, a longed-for instance of David’s admiration for something in Lena’s character, as opposed to her cooking or housekeeping. David finally calls her “a perfect lady.”

After the funeral poor Samuel Bank was at a loss to know what to do, especially with the little girl Ruthy. Samuel suggested placing her in an orphan home. After considering the matter, Lena said, “No! I'll take care of the child.” She promised to raise her, though she had four of her own children to look after.

On October 23rd Belle was taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital. She gave birth to a daughter but the child died soon. Belle was suffering from bronchial pneumonia.

On November 10th a stiff cold wind was blowing, stripping the leaves from the trees and from the trunks and branches. A dull sky cold like metal. Snow flurries were falling on the ground. David got a telephone call that Ben-Zion was sick. David came and took him to Dr. Abramson. He seemed rather numb. The muscles of his throat seemed contracted, and he could not utter a sound. The doctor gave Ben-Zion medicine and he began to feel better.

Well, three of Lena’s children have already left home.

Was Belle’s pneumonia the reason that the baby died?Julian: I don’t know, but according to my mother, Belle’s tiny size had something to do with her miscarriage — her hips were too narrow, according to my mom. This is likely to be family lore, though . . .

I don’t know, but according to my mother, Belle’s tiny size had something to do with her miscarriage — her hips were too narrow, according to my mom. This is likely to be family lore, though . . .

I can only assume this is one of Libshe's brothers, hence Loss, not Laas, which is a Scandinavian spelling. Presumably it’s a coincidence that they are at the Swedish Hospital!