Albert and Ruth

On December 5th, David received a letter from Albert informing him that he had written to Mr. Seekind [in the stockyard] asking for a job and that he had promised him one. On December 8th, Albert and Ruth came home at 5:45 p.m. from Waco, completely discharged from the army. On December 10th, Albert went to work for Mr. Seekind.

Albert and Ruth now had to settle down to the reality of living. It was a critical time for them. Most youngsters launch into matrimony with little preparedness or none at all. Hence the results are wobbly. Neither knows what is expected of them, nor what is right and what is conducive to mutual happiness. If they want to get married, they simply get married without any reasonable consideration regarding a steady position to finance new conditions and responsibilities. And, when all is said and done, with only a sketchy knowledge of each other’s mind and soul.

Our schools have totally failed to train minds. So have most homes. No wonder then that there is the present worldwide confusion through which we are struggling.

Ruth’s advanced age when marrying was a subject of discussion in our family.

Al is now 24, Ruth 27. If that’s advanced, I must have been a geezer when I married at 32. On the other hand, for the times, as well as for the family, it was perhaps slightly older than typical. Leah married at about 21, Lena at 24.

What does he mean here by “minds”? I think he means character.

For some months Albert and Ruth had been praising each other, finding perfection in each other. Rushing together for their scanty week-ends, and occasionally evenings spent with the fever of youthful enthusiasm. But now they had to be together, they had to like each other every hour the clock around, in every mood though sometimes feeling disappointed. True, they both had their faults, and more serious than their faults was the possibility that in their education there had been a serious deficiency. Perhaps Ruth’s mother was never herself a good or intelligent housekeeper. Naturally in such a case she had not prepared her daughter to be a good wife. How should she possibly guide her daughter to successful womanhood?

It seems impossible for David to say anything nice about anyone, even his daughter-in-law’s mother.

Not clear what he means by “education” and what he expected for a woman of the time. Again, he seems to criticize women when they are insufficiently traditional, and also when they are insufficiently modern!

How to square this with his enthusiasm for Belle, isn’t she doing things on her own? And his critiques of Leah’s parents back in Europe for not giving her a better education?

Actually, what is Belle doing? There has been no reference to her working or going to school. Is she focusing solely on her “first mission in life,” as described by David below?

A great amount of pride was built up by the World War. Some rose from poverty to wealth. Many became rich and became social climbers trying to ape the Joneses. There seemed to be only a few pure and fine characteristics developed in homes nowadays.

After three months of petty quarrels, jealousy, laziness and criticism, the success of Albert’s little matrimonial experience seemed about to be blighted in the bud. After such a beginning it is only a question of which one first will summon up courage to sue for a divorce.

The first mission a woman can have in life is to make some man a good wife and to run a home the way it ought to be run. Be a real mother to her children. Those women who go out and do things on their own are freaks. No one has any use for them. They are out of place when they are trying to push their way into circles where they don’t belong.

Married happiness is never found ready-made, tied up in tissue papers with pink ribbons. Not any more than other happiness. The fact that those two were thoroughly drawn by passion to each other and that they were young and happy in starting out in life with all their wedding presents, with the little money and the memory of that darling wedding and rapturous honeymoon, was some aid to happiness. If the young folk like each other fairly well that helps some too.

But beginners nowadays expect too much. They must assume now the kindly and limited attitude that must be reached sooner or later . Such a marriage state cannot endure. In their hard months of adjustment they had to begin with finance, pills, and bills. Half of their management fails because of inexperience and insurrection.

Perhaps they worried over what their friends would say or think of them, of their poverty or wealth. You are going to lose most of them sooner or later anyway unless they are really worthwhile, and if they are [worthwhile] you cannot lose them. If the young wife is clever and loves her man, it will be only a few months before the young husband will be boasting of his wife’s housekeeping and cooking.

As for the young husband, he must never knock his wife’s housekeeping or make invidious comparisons between it and his mother’s. But on the contrary he must be forever praising her domesticity and openly congratulating himself for having married the only woman who combines the attractions of Venus and Minerva. Even when the steak is leather and the bread a cinder, he dare not complain; at most he may merely remark that the meal is not up to her usual standard of perfection. But a wise woman should know. If a man is rankling with desire and ill feeling towards you, you cannot win him to your way of thinking with all the logic of an Aristotle. A domineering, nagging wife ought to realize that people won’t change their minds.

Deborah:

Where were Al and Ruth living? Why is David so well informed about their relationship?

Throughout the passages in the next couple of pages, what we see is that David is upset with the changes in women’s roles during the war.

This attitude was what our grandmothers and grandaunts lived with. It’s amazing to think of the changes that have happened since David wrote these words. Consider the five generations of women directly connected to this diary: from Leah, who represents the traditional feminine ideal; to Lena, who shows signs of rebellion in her temper flare-ups and serious depression in her physical ailments; to Helen, who rebels directly by leaving the family and ultimately eloping with a socialist and atheist (i.e., a man theoretically unfettered by traditional attitudes); to my mother, Beth, who manages to get into college because neither of her brothers is interested, secures a post-graduate degree, and experiences autonomy in her marriage to my father; down to me, a woman with a couple of post-graduate degrees, a profession, and a husband who shares that profession and the housework, as well.

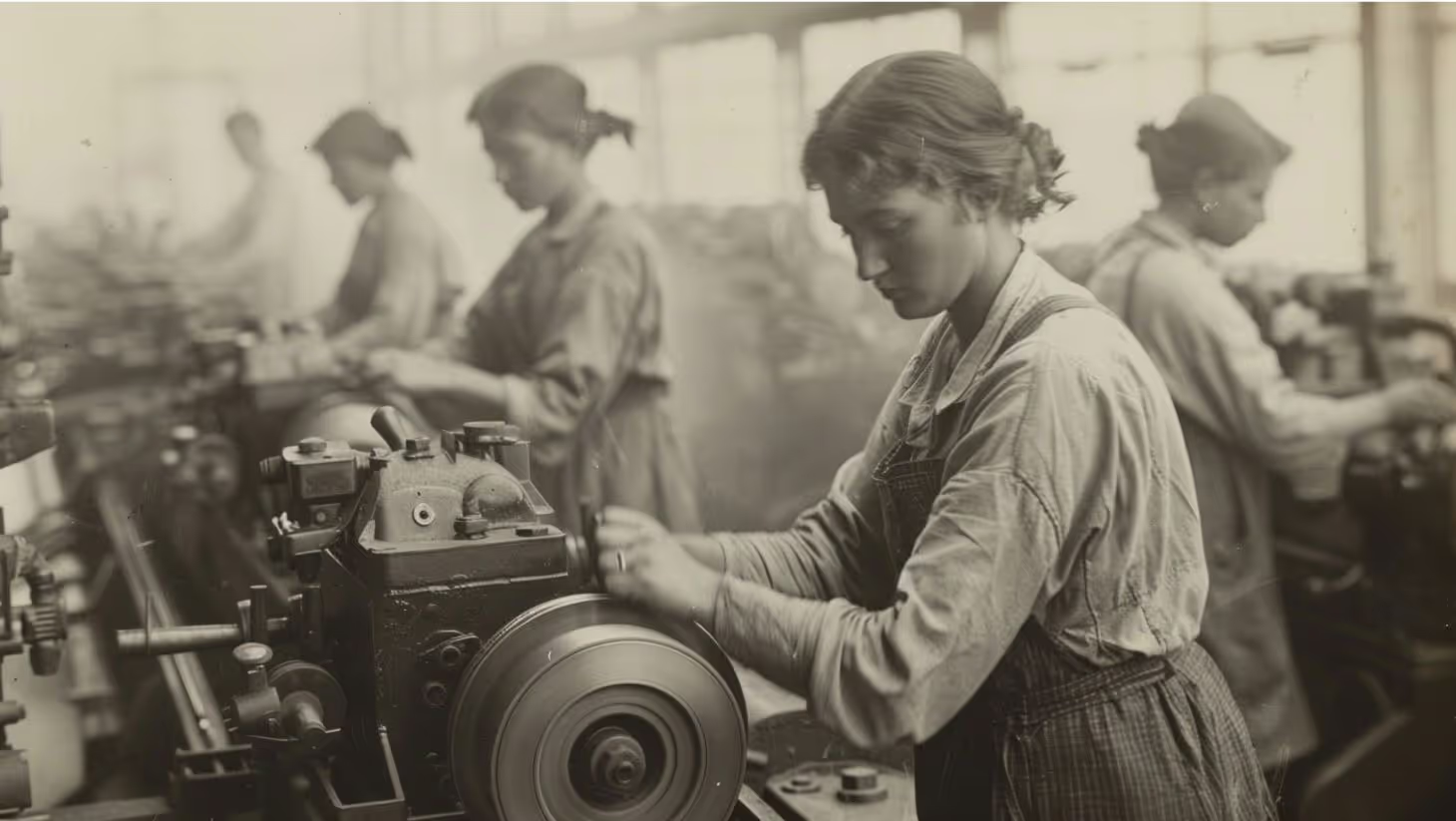

Helen’s struggles fascinate me because they signify the changing social context in which she was living. Women were in the midst of securing the vote, we were driving automobiles, some of us were working “men’s jobs” in factories during WWI. Add to all of this that Helen was a first-generation American-born child. (Belle was first-generation, too, but she was the first born, thus held more securely under her parents’ sway). By the time Helen’s childhood began, her parents were fully Americanized, permanently settled, and financially secure. In short, Helen was a truly American girl, whereas Belle had the tinge of the old world upon her. Helen took an important step forward in our family, in my opinion, by asserting her independence.

After the War

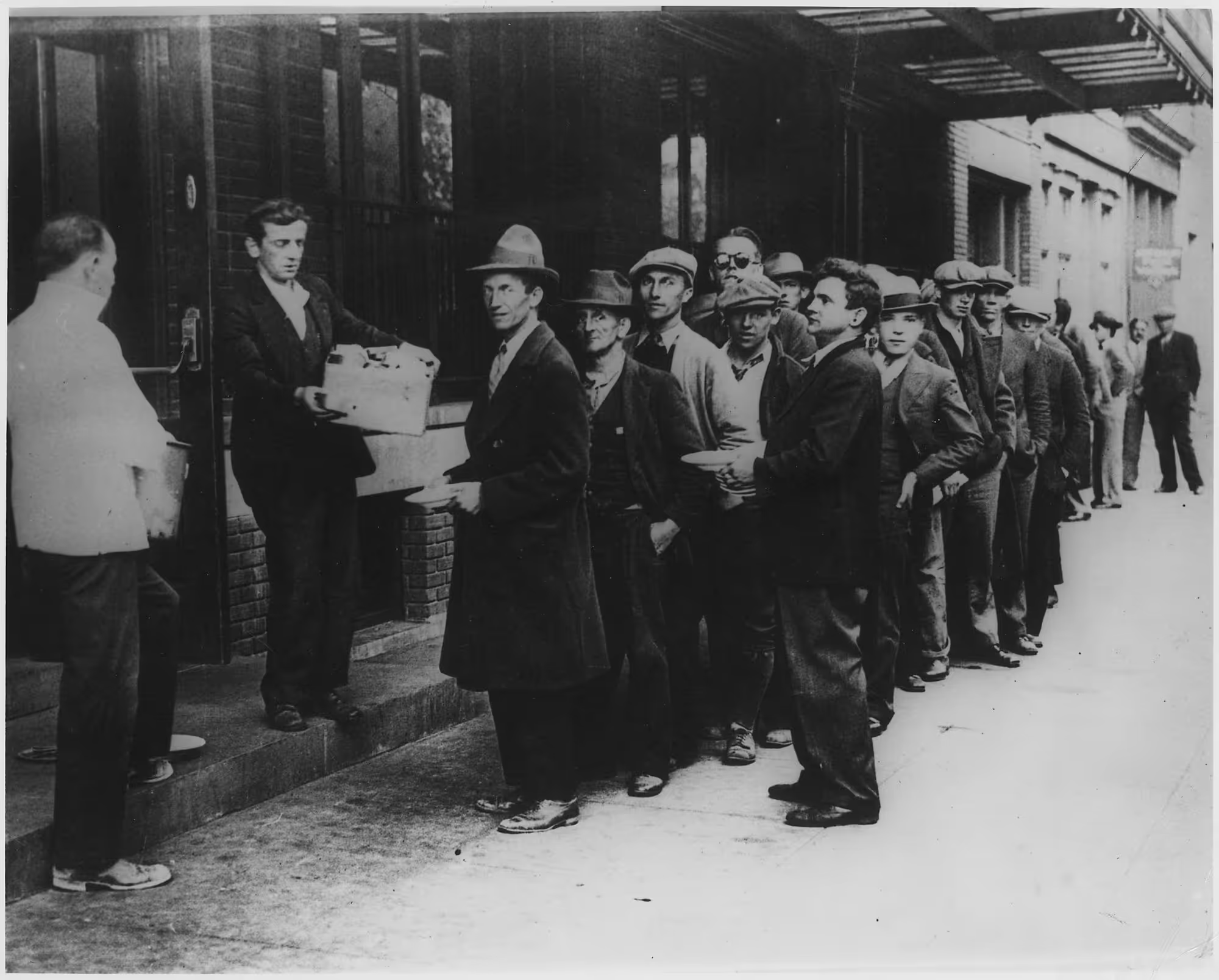

After the Armistice was signed and the war was declared ended on all fronts, a period of adjustment came which brought grief and travail. Business began to stagnate and came to a total standstill in many industrial centers. Fortunes that were made overnight toppled, popped out of sight like soap bubbles. Men who were once considered wealthy came down almost to the breadlines. All war contracts were cancelled. Factories and shipbuilding yards were closed, throwing thousands of men and women out of employment; and the many returned soldiers, those ready, willing and able to work, often found their positions filled by girls and married men.

That [situation] had not come from above from an autocratic region. It flowed in all directions like a devastating sheet of lava coming from countless fissures with volcano-like clouds of smoke and stifling sulphur fumes.

There came a period of restlessness. Agitators began to incite the people. Some people, of course, are made revolutionary by philosophical conversations. Some by dark and tender despair. And a few by personal information.

Fathers were spending their salaries in saloons and coming home for meals at late hours. All over the nation men were acting in like manner. Everything always moving. The world always changing so that it won’t be what it is now.

Sean

As for the volcanic imagery, I think he’s saying here (rather melodramatically) that there was no one cause or person to blame for the situation, it was a holistic societal economic collapse.

David found his business had suffered a slump after the war. He was interested in life about him. He could see clouds of black reaction upon the land growing thicker and thicker, threatening to envelop in their darkness the entire social fabric.

“Black reaction,” does he mean right-wing politics?

Or just depression and unrest?

The Armistice brought joy as well as sadness to thousands of homes. Mothers, wives, and sweethearts waited for their dear ones to come back from the various fronts. Many were maimed, crippled and wounded. They received a tender welcome. There were many who were doomed in sorrow to wait for the return of the bodies of their loved ones, if they were fortunate enough that the bodies had been recovered from the battlefield and brought back to rest in American soil.

During the war most able-bodied young men were recruited for the grim adventure, if not willingly, then forcibly. They were wanted as grim fodder, and it must be acknowledged that in the fighting most of them went gladly with a sense of exaltation or in a spirit of self-sacrifice for interests and ideals beyond their own little selfishness, because of the thousand passions beyond all reason instinctive and terrible in the herd.

Women stepped into the shoes they had left behind them. All their places were taken in factories, fields, shops, and offices. The women kept the home fires burning and learned all there was to know about the work of men. And nine out of ten they were better because of neater minds, nimbler fingers and less repugnance for drudgery.

Many of the soldier boys who had been getting money from home and gifts from friends became lazy. They led a shiftless life while abroad and were unable to do a day’s work. Some of them were too proud to work at anything they could find. But more, indifferent and dissatisfied with the turn of events, adopted a revolutionary attitude, saying, “We saved our country. We staked our lives to shield your hides. Now you must pay us for doing that!”

Since the world had grown crazy, fighting and getting and spending and losing on a scale as it never had before, men [had] schemed to shape events. But now events were shaping men. No one was equal to what was happening. It looked as if the Lord himself was taking a hand at it.

This is more feminist and modern, and contradicts what he says above.

Soldiers in khaki were hugged with abandon by middle-aged women and kissed by pretty girls. There were thousands of others who were walking the streets of the world. Men married and single, rich and poor, whose chances were ruined by grief that was none of their own fault. Most of them did not even know it. Nobody seemed to pay for anything they bought. It all was on installments. Buying and selling. The scrubbing women in the boarding house buy silk stockings, and buy them on installment. They would not be caught wearing cotton stockings.

Women are the class markers. If they get the money to buy the clothing of an upper class, they could marry up. The entire issue of class-appropriate clothing for women, especially young unmarried working women in the Twenties, is a huge topic in the women’s history literature.

Men did not talk much about religion. They talked of everything else – how to reform the world and how to save it from passion, from Bolsheviks, from cocktails, from Communists . They talked of women, of course, and of getting money. But everything they talked about had nothing to do with God.

There has come over the country, David thought, a wave of self-indulgence coincidentally with the great wealth that came to us.

I am struck by the familiarity of these feelings. Every generation thinks it’s headed for doom, right?

To add to the difficulties of adjustment, the Prohibition Amendment was appended to the U.S. Constitution. This was ratified to take effect in 1920. It brought about an endless multitude of stills, large and small, with an army of bootleggers and racketeers. It corrupted justice; a crime wave swept over the nation. There was an almost total bankruptcy of morality. “[Gideon’s Army of] One Hundred Percenters” and the Ku Klux Klan were like worms that have eaten holes in the shell and poisoned the kernel of our national conscience. [“100-percent Americans” (based on the biblical book of Judges) was an arm of the KKK concerned with wiping out Roman Catholicism.]

There had been, of course, the usual flotsam and jetsam of undesirables, but men and women who were worthwhile had kept to themselves.

True, David mused, we don’t live in the dark ages any longer. But we are not allowed to enjoy our lives in peace in our own homes, for everywhere in the world armies are on the march to destroy what we have built with so much labor.

During the World War the Jews became the international football, being kicked from one land to another, tossed from one province to the next. In Russian Poland they were accused of being “pro-Germans”; in Austria they were charged with being “pro-Russian.” Their rights were trampled underfoot and their homes burned and pillaged under pretense of espionage and treachery. Hundreds of prominent Jews were held as hostages, shot, knouted, hanged and buried alive. Women were outraged. When they fled, hounded by their own military authorities, they wandered into towns outside the “Pale.”

Where the Serb and Belgian had one enemy before them, the Jew had two: one in front and the other behind. The Jews paid double toll in gold and treble toll in lives. Officials broadcast anti-Semitic propaganda, printed pictures of Jews killing Christian children to obtain ritual blood. Tales which were reeking with blood and fire were told, describing 215 [confirmed] pogroms.

So what are David’s politics? Is he a liberal? Is he critical of the war, or in support of it?

As for the volcanic imagery, I think he’s saying here (rather melodramatically) that there was no one cause or person to blame for the situation, it was a holistic societal economic collapse.