Ben Zion's Despair

Ben-Zion became disheartened at the adverse conditions which fate put in his way, but he placed his trust in God, who cares for all creatures from the mole to the elephant, and far more for good and pious people. At last he found consolation for himself. He cast his lot with the Chassidim, a Jewish sect whose motto is “cheer and optimism” in the home as well as in business life in contrast with the Mithnagdim, who are somber and sad, sticklers for all traditional and religious observances. The Chassidim are a very pious class and well versed in Hebraic lore and culture. They were proud of their Tzadik, their spiritual leaders.

"L’Cho Dod": A song recited Friday at dusk, usually at sundown, in synagogue to welcome Shabbat prior to the evening services.

Ben-Zion joined the Chassidic Beth Hamidrash [prayer house], attending prayer meetings regularly thrice daily and they always had a memorial service, for some departed kin. They invariably served liquor and cookies after service, as such was the custom. Ben-Zion would delight on Friday evening, coming home from service, and greet the Sabbath by singing “L’Cho Dodi,” with a hungry soul. When coming home and finding Leah in her clean apron, the table spread with a clean cloth and the candles lit in the seven-branched candelabra, everything set to order, he would lift his voice singing to welcome the Sabbath angels, saying grace and eating his humble meal with contentment.

Now suddenly we are humble and content; the emotional tone in the rest of the discussion of family life has Ben Zion as an incompetent and Leah as spoiled and petulant?

Perhaps David means that all is redeemed on the Sabbath?

Zameter is a Yiddish dialect of Zemaitija (Samogitian), part of Lithuania.

In order to reduce expense at home Ben-Zion decided that David ought to learn a trade wherewith he could earn a living independently, though he was only ten years old. The father contracted him as an apprentice to a master tailor named Bradsky for five years. David was to get free board, lodging, and respectable clothes for his labor and learn the trade as well. The master tailor was a dissolute drunkard. While he conducted a large establishment with a staff of twenty men he was reckless in his ways. In those days human labor was cheap, the hours long and the work a hard steady grind. The lodgings were unsanitary and food was very poor.

The chance for rapid advancement was impossible for any apprentice under the prevailing system. The master’s method was to take on every spring four new apprentices, one to serve for [each of] four journeymen. These boys were treated like body slaves for the first year by the men. There was, in the same shop, one older apprentice called Berl the Zameter. He was a tall vigorous lad with a large head of curly hair, cold-mannered and taciturn. His eyes were black and piercing. They sent a shudder through the onlooker. He was of a bold and venturesome disposition. David was his only friend in that shop and the boys became quite chummy. Berl confided to David that he intended to desert and go to Salonica [now Thessalonika, Greece] where he had some distant relatives. Shaking hands with David, Berl the Zameter bade him goodbye with the hope that some day they would meet again.

This part of the story fascinates me, as it reveals the humble class origins of the family, and the lack of basic education of David's youth—making it all the more amazing that he became such a literate adult. Interestingly, we never learn how and when David acquired the skills that resulted in his voluminous writing decades later.

This part of David's narrative seems essential in piecing together an understanding of the high expectations he held for his own children. The anti-Semitism and hand-to-mouth existence he and his family experienced in the Ukraine surely influenced his perception of America as a land of "glory" and opportunity; thus, his children had a responsibility to embrace the opportunities placed at their feet. There is an (unattractive) shade of martyrdom that colors David's writing throughout, a trait that his father is not portrayed as possessing.

Ben-Zion had one hope. He heard so much of America, the “land of the free,” where everyone might enjoy the reward of his labor, and as the old Rabbis have said, “change of location leads to change of luck,” that he urged Leah to bear up with patience. He told her there was a silver lining behind every cloud and that there was no lane without a turning. They determined with all the power at their command to see America some day.

In Russia existence was often made unbearable by the newly awakened national feeling, which pounded against the Jew in waves of cruel persecution. Such trade as could be diverted into other channels by boycott was taken from them and the Jews daily grew poorer. Living became a precarious proposition and insecurity loomed large in everyday life.

Here is another clue to Ben-Zion’s story—a belief that moving to a new location would improve his fate. Thus, he had the stamina to endure so many relocations, and yet with each move he still was unable to fulfill the promise of better "luck" and so he continued to move on, and on. But now that we understand the dynamic combination of his personal values and the worsening of the economic and social conditions of his community, Ben-Zions decision to emigrate now makes total sense to us.

I am not sure that the causes of the pogroms in this era had anything to do with “newly awakened national feeling.” It is true that Jews in the Pale of Settlement were getting poorer; do we want to mention the REAL causes of the pogroms?

Economic conditions after the pogroms of 1881 went from bad to worse for Ben-Zion. The new police restriction on the people from different provinces, which became effective through the Ignatiev May Laws of 1882 imposed by Czar Alexander III, began in earnest, for the power of the law was personified in the gendarmes, who, armed to the teeth, patrolled the peaceful towns. Under such restrictions Ben-Zion had to move back to Courland, in Latvia, with his family.

Poor Ben-Zion! Fear and care had plowed deep furrows on his face and his back already was bent beneath the burden of law and lawlessness. Nevertheless he had a high sense of duty, so he began making every possible effort to raise enough money for transportation to Riga. David, who was working at tailoring, got a job in Libau. Herman, the second boy, also was apprenticed in a tailor shop, and the two older girls, Jennie and Freda, at dressmaking, and still there were two younger girls [Rose and Margaret] in the house.

It looked as if fate had new and strange problems wound in her skeins for Leah, and she was forced to renew the old-time slavery with a small bakery to aid the family’s support. In the meantime Ben-Zion corresponded with some friends in America. They had left Tukums for America two years before and were in Michigan. They advised him to come there, saying “America is the land which the gods have built, a continent of glory, filled with untold treasure and here is ample opportunity for you as well.”

David jumps head ten years here!

Now Ben Zion and Leah return to Courland. Why not back to her family, which would have been typical? (The bride’s family kest, which is housing and board for a young—or old but poor—family, I would think.)

It came about that in April 1883, Ben-Zion packed his satchel with his little earthly treasures, including a new blue velvet tallis sack, wherein he kept his prayer shawl, tefillin, skullcap and prayerbook, and he departed for America with high hopes, to see the fulfillment of his desires in the land where he need not fear nor take off his cap and bow for every petty brass-buttoned officer.

Before one could emigrate from Russia many painful and costly formalities had to be observed. A passport obtained through the governor was speeded on its way by sundry tips. It was itself an expensive document without which no Russian could leave the town.

As Ben-Zion left, Leah, with her pinched face, looked out and her sweet voice called to the departing father not to forget his dear Leah and the six children who would wait for tidings from him, be they good or ill.

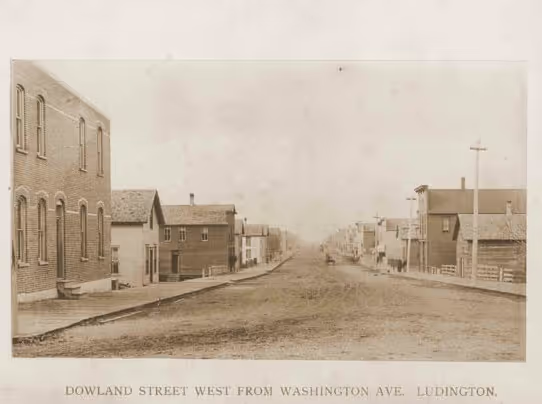

On arriving in Ludington, Michigan, his friend Jacob Bloomstock backed Ben-Zion financially for a stock of Yankee notions and tinware, and he blossomed out as a merchant, peddling among the sparsely settled villages, as was the custom of most of the newcomers in those days. That was the way they got their start in the land “flowing with milk and honey.”

Now we hear the answer to one of the most inscrutable questions about our family’s story: given their lack of wealth, how did they finance their immigration? We learn that Ben-Zion and four of his children all went to work to save for his passage, and even his wife Leah made her way back to work at the bakery shop. Ben-Zion had friends who had gone to Michigan, so that explains why he headed for that destination.

Despite my many childhood visits with my parents to the Temple of Aaron cemetery, I had never noticed Ben-Zion's gravesite until a few years ago, though it was always there, just next to that of David Blumenfeld. Now, thanks to the Diary, I can return to his tombstone and remind myself of the story of his difficult journeys north and southward in Eastern Europe, then to the American Midwest, the West Coast, and back to St. Paul, his final destination. Such a vivid sense of our family's passage through time: from Ben-Zion's youth in the 1850s, his immigration in the 1880s, David's writing the Diary in the 1920s, and now our stitching together of this very old story, in the second decade of the 21st century. Five generations, more than 150 years of history.

And I have only learned of this whole cast of characters, aside from a few references to her maternal grandparents by my mother, in the past two years. It is like unfolding a vast map of places and people to whom my brother and I are connected, and always were. To remain connected and to reconnect—to our kin who are here today and our cultural heritage—that's the key.

The humiliation of removing the cap is a strong theme in modern Jewish history; for instance Sigmund Freud hated his father for taking off his cap on the street once, it is a very famous "trope."

Also it is fascinating to see that the border between being a peddler and opening a shop plays a role at every stage in Ben Zion's life. When they decide to send David at ten to become a tailor, are they looking for an occupation for him that would have been considered ABOVE peddling?

OK, he is backsliding. As far as I can see, the flour mill was his prior job. This is quite a fall down the social ladder.

True. Yet, he would have had to be quite well off in order to land in America and then purchase land or start a business right away. It seems that we must either speculate that he was completely naïve about gaining a foothold in America (perhaps misled by the "happy talk" of his friend), or that he'd accepted that he would have to work his way up from the bottom in exchange for freedom from persecution and the opportunities available here. (I can't help but note that this situation of falling down the social ladder is still a common and major issue facing immigrants today, especially the college or vocationally educated, whose degrees or training are often considered inadequate in the U.S. or European countries).

His description of the difference between the Chassidim and the Mithnagdim (literally, "the opponents," which were the Talmudists) is totally slanted toward the Chassidim.